Financial empowerment is the key to increasing women’s influence in putting an end to child labour

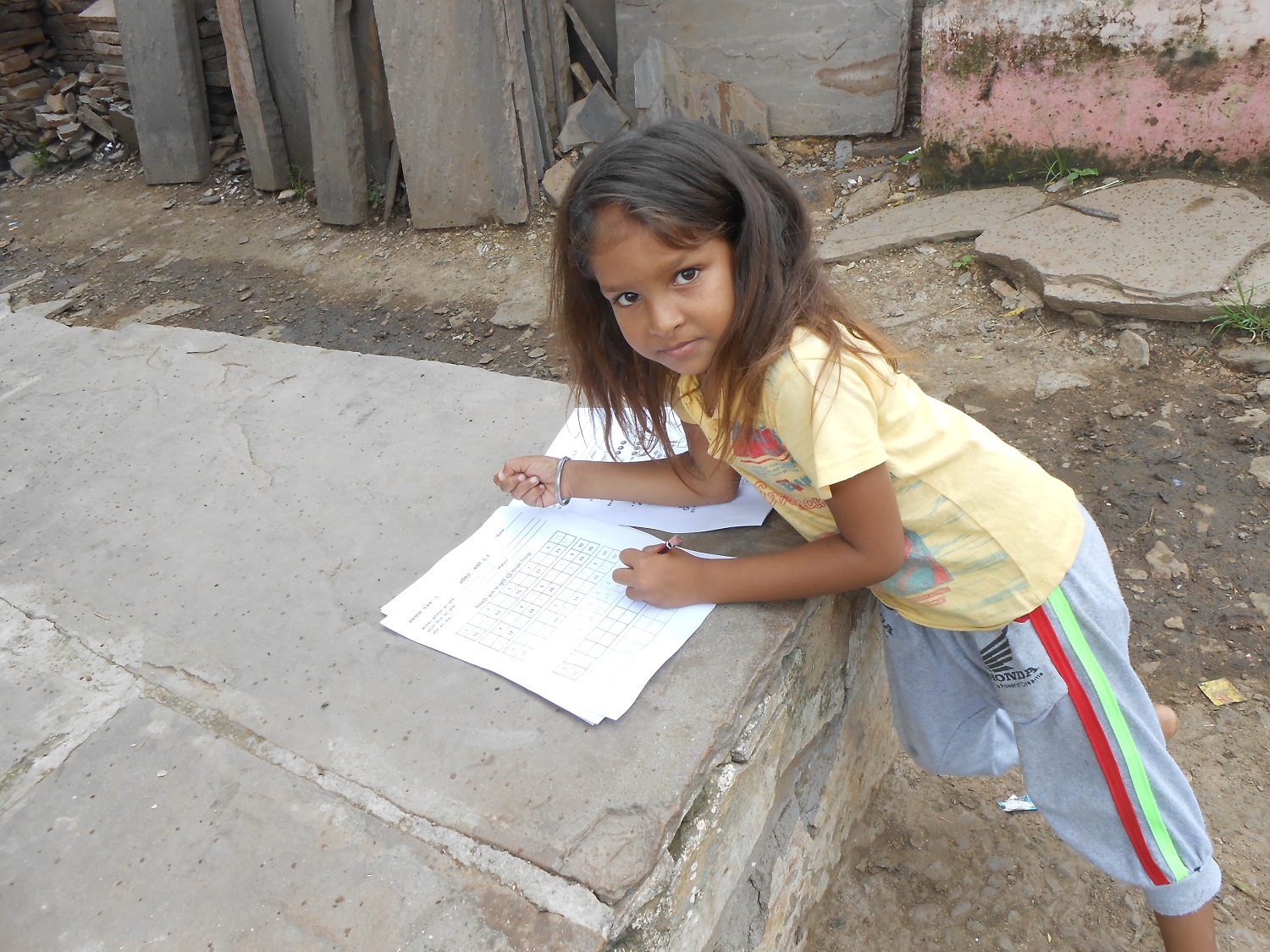

It’s not been easy in Budhpura—the centre of the cobble-making industry in Rajasthan and focus of No Child Left Behind, our project to support work to eradicate child labour in the natural stone industry.

India is reeling under the spread of Covid-19 and it is all the more to the credit of those involved in the work that progress continues to be made, in such difficult circumstances, with the community projects that are so valuable in improving lives in the stone industry.

Manjari is the grass-roots NGO that operates in the heart of Budhpura with a team of fifteen who work directly with mine-workers, their families and local businesses.

Manish Singh is Manjari’s Secretary. “Wave one of the virus did not bring any difficulty,” he says, “but wave two has been disastrous. We do not have much liberty to move in the field, so whatever volunteers we have are managing the work.”

Although the ultimate aim of their work is to eradicate child labour, the success of this depends on improvements being made in many different aspects of life for those who live and work in the area—in health, education, and income, to name but a few.

Enter Self Help groups. Over the past months, support has continued for these wherever possible. Whereas self-help groups in this country are initiated with many different purposes in mind, in India the self-help movement began with the focus firmly on women’s empowerment. “Given the socio-economic and gender disparities we have,” says Manish, “it was considered a tool to bring about change in the life of women.” This is exactly their purpose in Budhpura.

Varun Sharma is Programmes Director of Aravali, the agency that works at state level, acting as an interface between the government and grass-roots organisations like Manjari, while also helping the groups to develop their reach. “If children are at the heart of our project,” says Varun, “then protecting their mothers are also one of the key roles of our programme. That’s why we form self-help groups.”

In normal times, neighbourhood groups of around ten to twenty women meet every month to discuss matters of common interest. “When you bring them together, then the first thing is they must feel that they are a part of group, and the group has an agenda to fulfil. How long can you sustain these groups without an agenda?” points out Manish. “That’s a practical problem we have. So, we keep on taking up different activities.”

Each meeting covers a women’s issue—including family planning, menstrual health, and hygiene—but also has a business agenda.

One of the most important items on the agenda is inculcating saving habits; economic empowerment has a major part to play in making women’s voices heard. “If they have a role in family decision-making because of the money they have, then it makes a difference to their position within the family,” says Manish.

“We’ve found economic empowerment is very much necessary when we work with women and children,” says Varun. “If she is earning but she’s not saving, at the end of the day a woman doesn’t have the power to negotiate, power to expand—so, she’s only an earner. An earner should be a decision-maker, I think.”

The effects are gradually being felt and Varun has noticed that in areas where women have become more powerful financially, female empowerment overall has been greater.

The dream is that, in giving women a voice and the information they need, women will be able to work together to resolve some of the issues they face—domestic violence and child marriage being just two.

Helping women cannot be done in isolation, however. Everyone in the community has to be brought on board, and the approach is always to be gender-sensitive. “When we say gender-sensitive,” explains Manish, “it means involvement. For us gender is something that involves women and men both. If you think you are empowering women, but the one who is holding the power is not being sensitised, then all your efforts are useless. It is the men who are holding the power.”

So, Manjari works with labour groups too. When these groups—largely made up of men—meet, Manish and his team talk to them, not only about labour rights, but about gender justice and their responsibilities as men in society.

“We work with men and boys,” says Manish, “so their perception of women is changed.”

Read more about the work of Manjari and the progress that has been made in Celebrating Budhpura.

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/all-porcelain.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/luxury-italian.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/premium-italian.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/budget-porcelain.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/large-format-porcelain.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/wood-effect-porcelain.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/porcelain-planks.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/porcelain-setts.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/browse-all-paving.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/stone-paving.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/interior-tiles.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/stone-effect-porcelain.png )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/wood-effect-porcelain.png )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/grey-porcelain.png )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/beige-porcelain.png )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/dark-porcelain.png )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/light-porcelain.png )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/patio-grout.jpg)

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/primers.jpg)

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/porcelain-blades.jpg)

/filters:quality(90)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/drainage.jpg)

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/cleaners.jpg)

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/all-stone-paving.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/all-sawn-paving.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/all-riven-paving.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/indian-sandstone.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/limestone-paving.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/granite-paving.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/slate-paving.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/yorkstone-paving.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/stone-pavers.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/cobbles-setts.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/plank-paving.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/paving-circles.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/bespoke-paving-1.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/edging-stones-1.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/prestige-stone.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/grey-blue-stone.png)

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/swatch-black-dark.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/swatch-buff-beige-white.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/sealants.jpg)

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/all-clay-paving.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/alpha-clay-pavers.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/cottage-garden-clay-pavers.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/kessel-garden-clay-pavers.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/artisan-clay-pavers.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/grey-blue-clay-paver.png )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/red-brown-clay-pavers.png )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/beige-buff-clay-pavers.png )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/composite-decking.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/designboard-decking.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/classic-designboard.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/brushed-designboard.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/grooved-designboard.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/millboard-decking.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/grey-decking.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/black-charcoal-decking.jpg)

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/brown-decking.jpg)

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/all-build-deck.png )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/stone-cladding.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/all-garden-walling-1.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/facing-bricks.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/garden-screening.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/all-steps-coping.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/stone-garden-steps.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/sawn-steps.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/riven-steps.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/yorkstone-steps.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/bespoke-steps.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/porcelain-steps.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/off-the-shelf.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/stone-coping.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/sawn-coping.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/riven-coping.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/yorkstone-coping.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/bespoke-coping.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/stone-pier-caps.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/porcelain-coping.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/all-bespoke-services.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/bespoke-paving-2.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/bespoke-steps-1.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/bespoke-coping-1.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/edge-profiles.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/masonry-services.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/deluxe-pergolas.jpg )

/filters:quality(60)/mediadev/media/menu-pics/proteus-pergolas.jpg )